We don’t have to feel small. Southern Vietnamese modernist architecture already carries the confidence of Vietnamese pride

To walk through the older streets of Saigon is to realize that Southern Vietnamese modernist architecture has never been peripheral. Shaped by climate, material intelligence, and an open yet discerning embrace of modernism, it reflects a level of architectural confidence that speaks for itself. This is not a borrowed language, nor a diluted version of global trends, but a body of work formed by capable Vietnamese architects who understood their context deeply and responded to it with clarity and skill. In conversation with Mr. Mel Schenck, an American architect who has spent decades observing, researching, and living alongside Vietnam’s architectural evolution, this truth becomes unmistakable. Vietnamese architects are highly capable, and Southern Vietnam’s modernist architecture is a legacy worthy of pride, without comparison and without apology.

How would you introduce yourself?

Well, let’s see. I’m an American. I come from America, the state of Montana. Most people don’t know where Montana is. It’s up by the Canadian border, just east of the Rocky Mountains. The Rocky Mountains go through Montana. Most of it is prairie, though — farmland, oil. So, that’s where I’m from.

I got my bachelor’s degree, a Bachelor of Architecture degree, at Montana State University, and that was in 1970. What you call the American War was still going on then. At that time, the American government was drafting young men like me and forcing them into the army because they didn’t have enough soldiers otherwise. They had a lottery system. They assigned numbers — 365 numbers, one for each day of the year.

You would look at your number, and my number was fairly low, which meant I had a very high chance of being drafted into the army. But I had just graduated from architecture school, and I thought, well, I don’t know anything about guns, but I know about construction. And I knew about the huge American construction program in Vietnam. So, I applied to the Navy to be an officer specializing in construction. They accepted me. So instead of going into the army, I was in the Navy.

I knew I would be doing something that involved architecture, primarily construction. I came here for a year, from 1971 to 1972, and lived in Saigon, but I had construction sites in Da Nang and Hoi An. Imagine that — Hoi An in 1972. I had no idea about Hoi An at that time. We built housing for Vietnamese Navy personnel out on the beach. There’s a big five-star resort there now.

Then, traveling down the country between Phan Thiet and Vung Tau, I had a project in a town called Ham Tan, which I think is now called La Gi. I also had many projects in what is now Dong Nai Province, and then up into what was called Bình Long Province at the time. I had a couple of projects up there, as well as projects in Vinh Long.

So, all up and down the southern part of Vietnam, I saw a lot of the country. I was constantly traveling. During all that time, I never saw the war, which was lucky. I had some good projects. I administered 21 construction contracts for Vietnamese contractors across the country. I didn’t work on the huge American construction program because it was being closed out by the time I arrived. That was handled by other officers. I focused on Vietnamese construction projects.

When you first came to Vietnam, what about Vietnam made you feel a passion for discovering its architecture? What was special about it?

Well, I had two primary reactions. From the first day, coming from the airport down to our headquarters on Hai Ba Trung Street, I had two reactions right away.

The first was that I was astounded by the amount of modernist architecture here. We were going down what is now Phan Dinh Phung Street, near the intersection of Nguyen Kiem, Phan Đăng Lưu, and Hoang Van Thu. From there on down was a tremendous collection of modernist shophouses. I couldn’t believe it, because I had just graduated from architecture school in America. There isn’t much modernist architecture in America. There are obviously some very famous works by Frank Lloyd Wright and other American architects, but nothing like the quantity of what I saw here.

The place where we stayed was on what is now Nguyen Trai Street, close to Cong Quynh. Again, I walked down what is now Nguyen Trai Street and Le Thi Rieng Street, and it was 100% modernist. I was shocked. I couldn’t understand how this had happened. It meant that people here had embraced modernism. They liked it. Whereas in Europe and America, people generally don’t care about modernism, or they don’t like it. So seeing that difference was shocking.

The second reaction was related to urban planning and density. I grew up in Montana in a small town of about 3,000 people. The nearest town was 40 kilometers away. There weren’t many people in the state. When I came here, by the time I left, there were about four million people. For the first time in my life, I was in a big city, and I loved it. I loved the density and being around so many people. Between those two reactions, it was a great year for me, and I learned a lot about construction as well.

You mentioned holistic architecture in Vietnam. Could you explain more about that?

About twelve years ago, you probably know the architecture firm Tropical Space. They designed a house in Da Nang called the Termitary House. If you remember what that house looks like, it’s essentially made of red brick, with a lot of open space and many small openings. Their idea was that termites are able to moderate extreme environments like Da Nang — very hot in summer and cooler in winter.

They do this by creating a double-wall nest. When you look at the Termitary House, it has a double wall with about one or two meters between the walls. Ventilation openings all around the house moderate the environment so that air conditioning is not needed.

This approach is called biomimicry — looking at biology, in this case termites, and finding architectural solutions based on how they function. But it’s not only that. Because the house is entirely red brick, when you look at it, you don’t see parts. You don’t see windows. It doesn’t have visible windows. It has a door, of course, but what you see is a whole. One material predominates.

That is holistic architecture.

Modernist architecture, by contrast, is about parts — expressing parts and assembling them into a harmonious composition. Vietnamese modernist architecture is an assembly of parts, a vocabulary of elements developed by Vietnamese architects.

Holistic architecture is different. You design it as a whole, and it emerges as a whole. Tropical Space started this. There were two or three other projects that I noticed while looking at ArchDaily every day. I also started seeing comments left by foreigners about new Vietnamese architecture, and I realized something different was happening in Vietnam.

Big projects like museums and performance halls designed by Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid define holistic architecture, especially Zaha Hadid. When you look at her performance hall in Azerbaijan, it’s seamless. You can’t define individual parts. Even the ground becomes part of the whole.

However, star architects rarely work on houses or small schools. Firms like Tropical Space and KIENTRUC O Architects developed holistic designs at a smaller scale. I talked to them about this, and they had no idea they were doing what I call holistic architecture. But somehow, they understood the intellectual force of our era — the Information Age.

Modernism is the architecture of the Industrial Age, which has largely passed. In the Information Age, scientists, artists, and architects increasingly look at things as wholes rather than parts.

From your perspective, when listening to your concept of holistic architecture and modernist architecture in Vietnam, do these two books reflect contemporary ideas? What is the purpose of your next book?

The purpose of my next book is to show the world what holistic architecture is, because most architectural historians worldwide still have not fully realized it. They keep calling Frank Gehry’s work, in particular, deconstructivist, which it is not. Deconstructivism is simply another assembly of parts; it is still modernist.

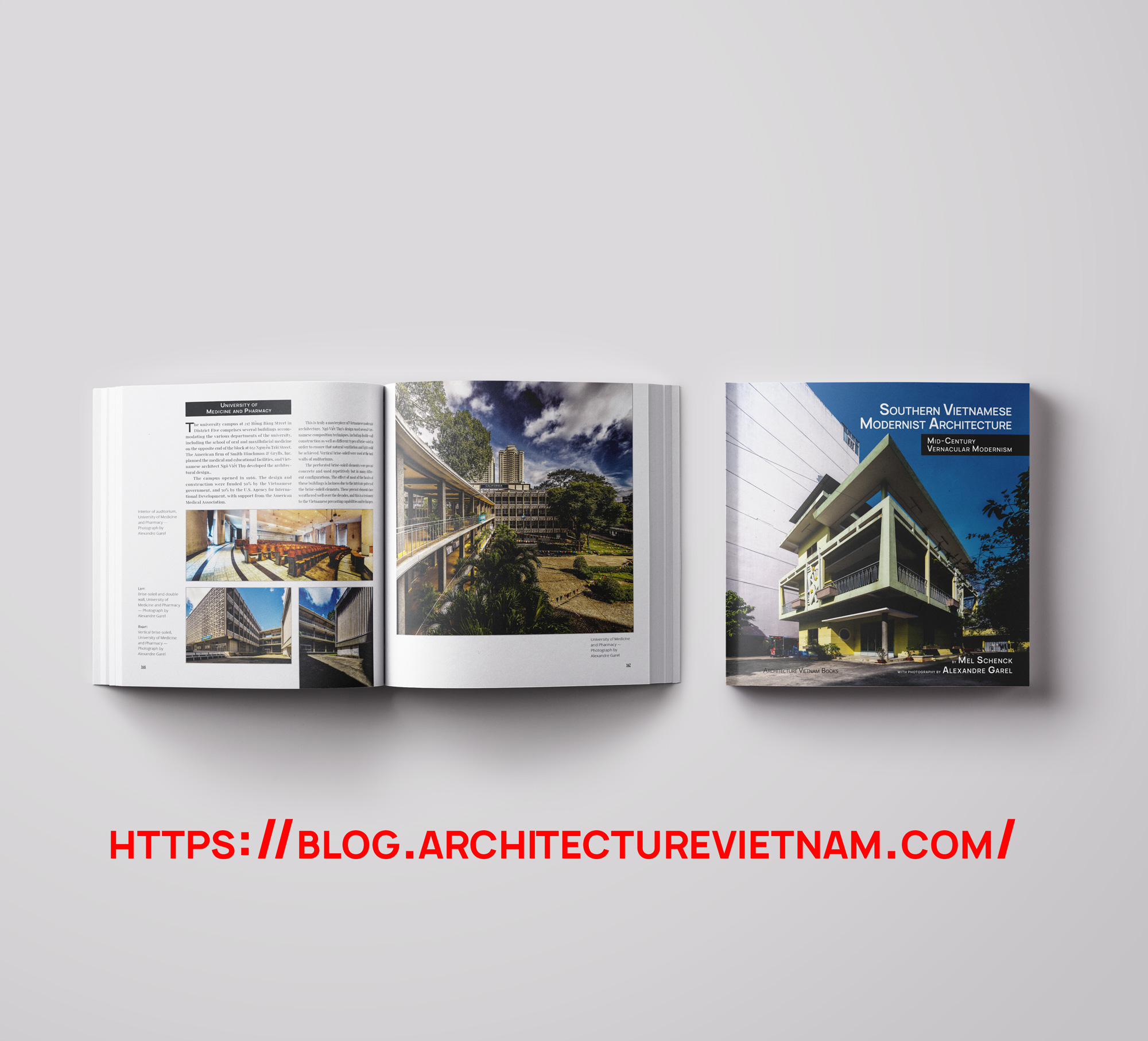

Many people consider Zaha Hadid’s work to be a higher level of modernism, but they cannot break out of the mindset of the Industrial Age. I began researching holistic architecture after I finished my modernist book, which was published in 2020.

By then, I was about 75 years old. I’m 80 now. During this time, memories from my childhood, my university education, and my professional life started flooding back. I later learned that this often happens to older people. These memories just come. I thought it was very interesting and decided to write them down.

I have three grandchildren in America whom I never see. They don’t really know me. So I decided to turn these memories into a memoir, an autobiography. The original manuscript was about 600 to 700 pages, which was too much, so I edited it down to about 500 pages.

Now my grandchildren have something to read someday, when they are old enough, to understand what their missing grandfather is like. Writing the book took a couple of years. After writing it, I had to design and lay out the book and then send it to the printer. I use a print-on-demand printer, so I don’t have to print and store thousands of copies.

Once that was finished, I returned to focusing on holistic architecture. Over the last few months, I’ve been reorganizing my thoughts on this topic. In the meantime, Vietnam has changed a lot. Because I work from home, I don’t get downtown or around the city very often anymore. Ten or fifteen years ago, I walked all over the city and knew it very well.

I’ve lived here for 20 years now, but I’ve lost touch with some developments, so I’m starting to get out again to see what’s happening. I still follow Vietnamese architecture through ArchDaily, Dezeen, and other platforms.

A lot has changed, as it has all over the world. Globalization has had a strong impact. Much of the architecture here since the 1980s has become more minimalist, similar to global trends. Unfortunately, many new high-rise buildings follow the International Style—bland and boring.

However, there are still very interesting things happening. I need to catch up, identify those projects, and then analyze them. In the new book, I will also explain why we have entered the Information Age and why holism has become important. It’s a very big topic, almost too big, but I’m going to do it anyway.

People always say that we must have a life goal. I was curious about your life goal. When did you find it? Was it in the past? And have you been pursuing that goal until now?

Even from high school — from the day I decided I wanted to be an architect when I was ten years old, I always thought about goals. I grew up in a small town and had no idea what architects actually did, but I knew they built things. The library in my town didn’t have any books about architecture. But my mother subscribed to magazines every week, including Better Homes and Gardens. So at least I could see what some interesting houses looked like, and some of them were modernist.

I would look at them and start thinking. I would say, okay, I’m going to design a firehouse. I would doodle and think in my mind: what do they need in a firehouse? Do they need space to park trucks? Things like that. Then I decided, okay, can I design a high-rise? So I designed a high-rise—just the exterior.

Doing things like that really helped me. Through that process, I developed goals. Obviously, my first goal was to graduate with a Bachelor of Architecture degree. Stay in school. Graduate. You needed a strong goal because I always wanted to be an architect.

So those were the first goals: I’m going to be a professional architect. I’m going to graduate with a degree. Then after that, my goals became: I want to be a member of the American Institute of Architects. I want to be registered as an architect—not just a graduate, but a registered architect. And then I wanted to have my own firm. I thought it would be in Montana. Forget that.

The life goal for me was simply to be an architect. That was it. And it still is. But there are things that go along with architecture, and goals change. Now my goal is to publish this book about architecture.

Nguồn ảnh: Saigoneer

Nhiếp ảnh: Phạm Vinh, Hiroyuki Oki